Capturing Rainwater for Household Use

The rainy winter that we’ve experienced after a long drought has brought stormwater and rainwater management to the front of everyone’s mind. We’re challenged in California’s Mediterranean climate by the yearly cycle of rainy and dry seasons, as well as periodic drought conditions. One of the ways that these challenges can be met is through small rainwater catchment systems that capture rainwater from rooftops in winter and store the water for future use.

Rainwater catchment systems have great potential benefit to residents and the environment. Since the Rainwater Catchment Act of 2012 was enacted, Californians have been allowed to use rainwater collected from the roofs of buildings for beneficial purposes. Rainwater catchment systems for non-potable uses, such as garden and landscape irrigation, have been built in Sonoma County for years. The Sonoma and Gold Ridge Resource Conservation Districts, through the Russian River Coho Partnership and related efforts, have worked with numerous landowners in rural areas to develop these systems to provide better water reliability for residents, while improving stream flows for endangered Coho salmon.

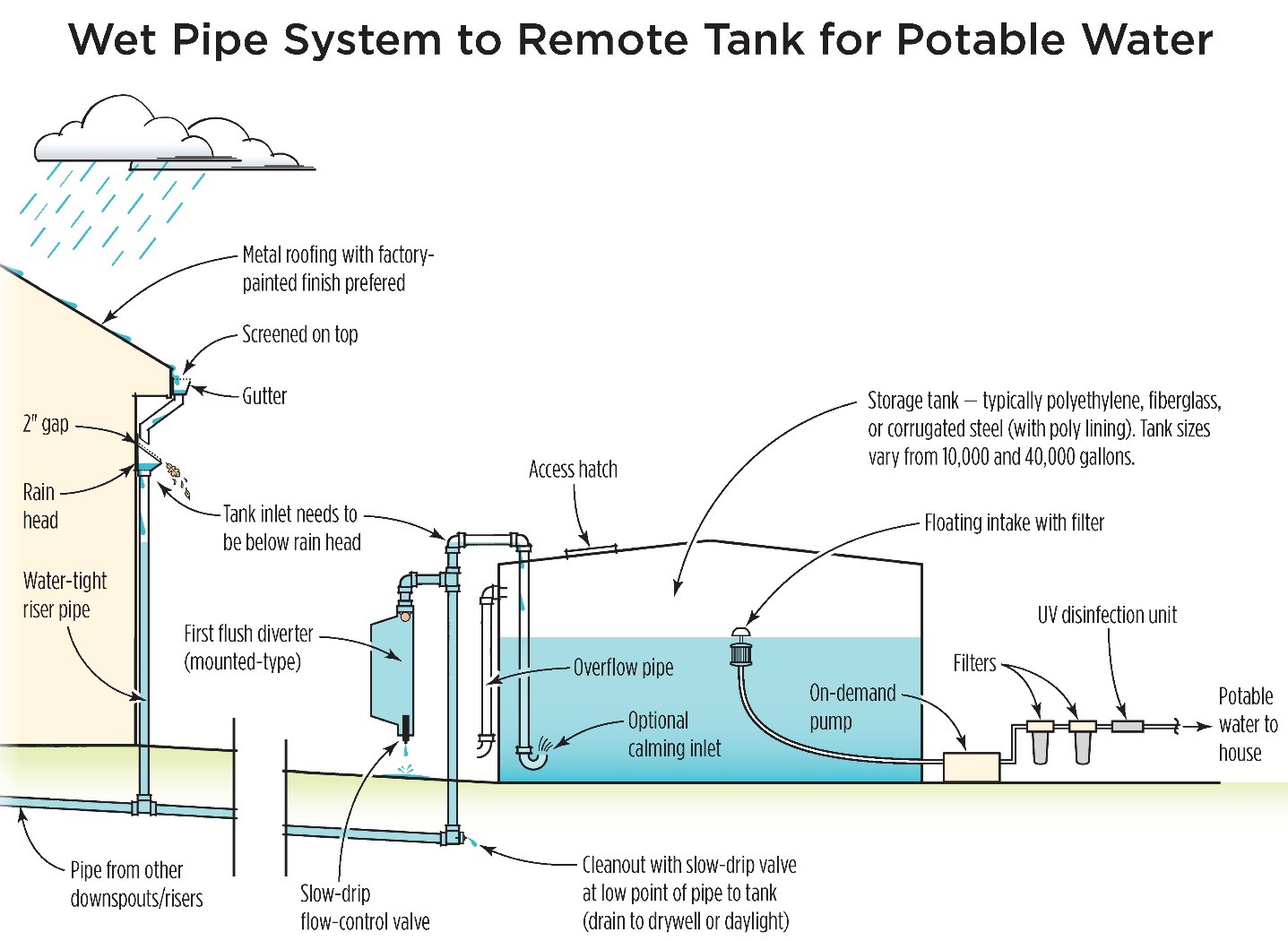

The County of Sonoma recently took another huge step toward water resource sustainability. In January 2017, the Permit and Resource Management Department adopted a new code section that, for the first time, gives Sonoma County homeowners the opportunity to legally build systems that capture rainwater for potable uses, such as drinking and cooking. The adoption of Appendix K of the California Plumbing Code now provides a framework for homeowners and businesses in unincorporated Sonoma County to use rainwater for potable purposes. Such systems would require a permit, approval of which would depend on many factors such as allowable roofing material; maintenance, inspection, and monitoring requirements; and minimum water quality requirements. Nonetheless, residents of unincorporated areas of Sonoma County now have a pathway to apply for permits to build those systems legally. If you live within city limits, check with your local planning/permitting department to find out if potable rainwater is allowed where you live.

While the costs of a rainwater catchment system can be high relative to more common water sources such as a well or municipality, the benefits of rainwater in some situations may outweigh the costs. A rainwater catchment system can provide a secure, reliable source of clean water. Some wells in water-scarce areas may not be able to keep up with demand, particularly in drought years. A rainwater catchment system can bridge the gap between water need and water availability.

The benefits of rainwater catchment to the environment are diverse. Most buildings, particularly in urban areas, direct rainwater from the roof into a stormwater sewer system which then drains into nearby streams and rivers. A rainwater catchment system bypasses that system by capturing rainwater and temporarily storing it to be released in the summer. This reduces the building’s impact on the water cycle, which is helpful to the environment in several ways.

- Decreasing the amount of rainwater that enters the stormwater system can:

- Reduce flooding;

- Reduce the soil erosion that pollutes the water and hurts coho salmon and steelhead; and

- Reduce stream channel incision that can adversely affect groundwater level.

- Increasing the amount, and changing the timing, of rainwater that soaks into the ground can:

- Improve groundwater supply;

- Improve streamflow in the summer, when it’s critical for fish and wildlife survival; and

- Contribute to reducing carbon in the atmosphere by promoting plant growth.

There are, of course, some very important considerations before deciding to build a rainwater catchment system for your home or business:

- How much water are you currently using? Are there any more ways to reduce the water you’re already using? Answering this question is the start of figuring how much water storage you need.

- How much water can you collect from your roof? The size and configuration of your roof is another factor in determining the storage size. Use the following calculation to estimate the amount of water you can collect from your roof:

Square footage of your roof x 0.63 x yearly rainfall in your area (in inches) = gallons you can collect annually (see Resources below)

- How much space is available to store water? Property size, zoning restrictions, and the terrain surrounding the building are determining factors in figuring out the size of the system.

- What is the cost/benefit ratio? Some homeowners pay a high cost to pump and treat groundwater, others must pay water trucks to bring them water in the summer. The costs that should be weighed against the potential benefit include: design of the system, permitting, construction, and maintenance. Depending on the location of the property, grant funding or rebates may be available to defray the cost of the system.

Resources:

To determine the average annual rainfall in your area, refer to this map created by the Sonoma County Water Agency:

http://www.sonoma-county.org/prmd/docs/landscape_ord/rainfall_map.pdf

For general rainwater catchment, water management information and a list of technical assistance resources, municipalities, contractors and consultants, and rainwater system suppliers, see the resource section of the Slow It. Spread It. Sink It. Store It! Guide to Beneficial Stormwater Management and Water Conservation Strategies

http://www.sonomarcd.org/documents/Slow-it-Spread-it-Sink-it-Store-it.pdf

California Plumbing Code Appendix K: Potable Rainwater Catchment Systems

http://www.iapmo.org/2013%20California%20Plumbing%20Code/Appendices/Appendix%20K.pdf